The advent of World War II in 1939 changed much of the record changer industry. Because of Roosevelt's embargo on trade to Japanese possessions, the record industry had to change the way they were making records. Shellac (used in 78-RPM records) was in short supply, so cheap binders were added to the material, and cardboard was sometimes embedded into the record. Also, the rims of the records, which had been rounded before, were now squared off. Most of the record changers produced before the war started breaking these records. The knives used to separate the records no longer fit between the (no longer rounded) rims, and instead chipped the edges of the records or broke them in half. The assembly line and Capehart changers also tended to break these records, and the RCA throwoff changers were the worst offenders, breaking most of the records they ejected.

The changer manufacturers had a sudden panic, and searched for more gentle ways of handling records. At first, they tried removing one knife shelf and substituting a plain shelf in slicer changers. This helped only slightly. But the overall result was the general development of what was then called the "push-type" record changer. The first of these was the Garrard RC-6 on the previous page. In this kind of changer, the record stack is held up by a ledge on the spindle, and by one side platform. To drop a record, a lever or cam in either the side platform (Garrard - UK, and Utah-Detrola and Admiral - US) or in the spindle (General Instrument, Westinghouse, and Motorola - all US) pushes the bottom record to one side and off of the ledge and platform. An offset in the spindle or a latch holds the rest of the records back, so they don't drop. This device handled the records gentler than the knives used earlier did. Variations appeared where the entire side shelf (Webster - US, and the original Garrard RC-6), or the entire spindle (Philco - US) moved to drop the record.

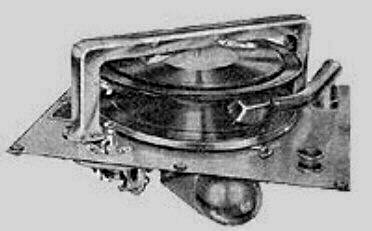

The Motorola, Silvertone, and later General Instruments (204 and 205) changers used a rotating cam in the spindle. The spindle cam changer is labeled "Spindle push and shelf" in the above diagram, except that the spindle had a rotating segment instead of a pusher blade (Diagram "Spindle B" shows a pusher blade). An example made by General Instruments appears below. But the earlier General Instruments 203 changer and the Galvin-Motorola B2RC had the first spindles with pusher blades.

An interesting sidenote is that many users of the rotating spindle-cam-type changers damaged their records by not understanding that they had to turn the top of the spindle between the changing and the unloading positions. They put the records on in the unload position and they fell, breaking out the shellac around the center holes. The rotating cams also wore the edges of the center holes, beveling them. Since the pusher blades did not do this, most changer manufacturers eventually changed to pusher blades.

- Maguire developed a system with two pusher shelves on opposite sides of the record and a notched center spindle. One shelf pushed the record into the notch to separate it from the stack, and then the other shelf pushed it out of the notch to drop it. The second pusher had a feeler to detect the record when it came into the notch. If no record was felt, the changer shut itself off. The shelves had to be turned for record size by hand. This changer did not work with warped records.

- Farnsworth came up with two variations on the push type changer. The

first, P-2, had two pusher shelves and a notched spindle, similar to the

Maguire. P-41 is similar, but has two sets of extra hooks that hold the

record on both sides after the pushers act, then simultaneously release it so

it falls flat. This unit also senses the pushed record, to check for the

absence of records for automatic shutoff. A control knob sets both shelves for

record size. This unit also worked very poorly with warped records.

The later Farnsworth variation was its P-51. It had two rotating shelves and a fixed pusher shelf. During the cycle, the rotating shelves moved under the record. Then the fixed shelf pushed the record to separate it from the stack. After this, the rotating shelves and hooks on the fixed shelf dropped it, after the weight of the rest of the stack had been removed from it. The record clamp on the fixed shelf activated automatic shutoff.

- Lincoln developed a 2-side assembly line changer that brought the

label-sized carrier arm to a feed stack of records, and used vacuum to pick up

the top record and put it on the turntable. Then it played one side, inverted

the turntable to play the second side (holding the record up with vacuum), and

then dropped the record onto a second stack of already played records. A

one-side mode was also provided, where the turntable inverts just to drop the

record. This unit played the drop-automatic and manual sequences, and shut

itself off after the last record.

This is the only record changer made during this time that had no change cycle cam. The change cycle was operated with a series of vacuum-operated valves and actuators. The end of each process in the change cycle started the next process. See page 3 for photos of a 3-speed version of this (which worked in a slightly different way, playing the slide-automatic sequence instead of the drop automatic sequence).

- Thorens created a 2-side drop changer with a rotating spindle and balancing disc. The turntable rotates in one direction, while the top of the spindle and the balancing disc rotate in the other direction. The head of the tonearm turns upside down to play the bottom side of the bottom record on the spindle ledge. The spindle design works in a similar way to those on the Collaro changers made after 1967, but it was actuated from the top. The changer shut off after the last top side was played. It had a velocity trip.

- Just a few months before the US entered World War II, RCA started making

its 2-side "Magic Brain" record changer RP-151. This was a drop-throwoff

changer that could play both sides of the records. It had one fixed shelf plus two

knife shelves for the dropping mechanism, but with no center spindle through the

stack. A guide centered the dropped record on the label-sized turntable that

turned it, and a forked pickup arm played first one side, then the other (the

turntable reversed rotation for the other side). Then the turntable tilted

and dropped the record in a bin.

The 2-side "Magic Brain" had to be adjusted by hand for record size. It could also be set to play only the top sides of the records. This "Magic Brain" stopped playing when the stack was over, not because it had an automatic shutoff device, but because there was no record there for the arm to play. The changer just sat there spinning its tiny turntable until you turned it off. The Magic Brain could use either the drop-automatic sequence or the manual sequence.

Very few of these were ever made, for two reasons:

- Factory production was commandeered by government for World War II shortly after manufacture of this changer began.

- Knife-type changers were breaking the substandard records necessitated by the lack of shellac. It was not made after the war because people wanted push-type changers.

Thus, World War II deprived us of the Garrard RC-100 (see page 1), the Capehart turnover changers (see page 1), and the RCA RP-151 two-side changers. The Capehart persisted a few years after the war, but people were warned not to change wartime records on them.

Garrard RC-70 shelf-push changer

Farnsworth-Panamuse P-2 double-push changer

Farnsworth P-51 shelf-push changer

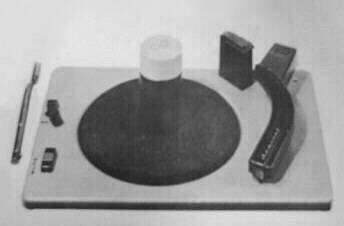

Utah-Detrola shelf-push record changer